In this section : Electrolyte Disturbances

Hyperkalaemia

Hypomagnesaemia

Hypophosphataemia

Hypernatraemia

Hypokalaemia

Hyponatraemia

Hypocalcaemia

Hypercalcaemia

Hyponatraemia

Last updated 4th March 2024

Overview

- Common electrolyte disturbance that is often difficult to interpret but usually easy to manage

- In all cases there is retention of water relative to sodium

- Usually mediated by ADH which is released appropriately (most cases) or inappropriately (SIADH)

- Urine Na and Osm are frequently requested but by the time you realise they haven’t been sent the hyponatraemia has usually resolved/been sorted

- If hyponatraemia is mild in range 130-135mmol/l there is no need to treat with the sole aim of increasing the serum sodium

Seven Point Assessment Plan

- Assess biochemical severity

- Assess for cerebral oedema

- Determine duration of hyponatraemia if you can.

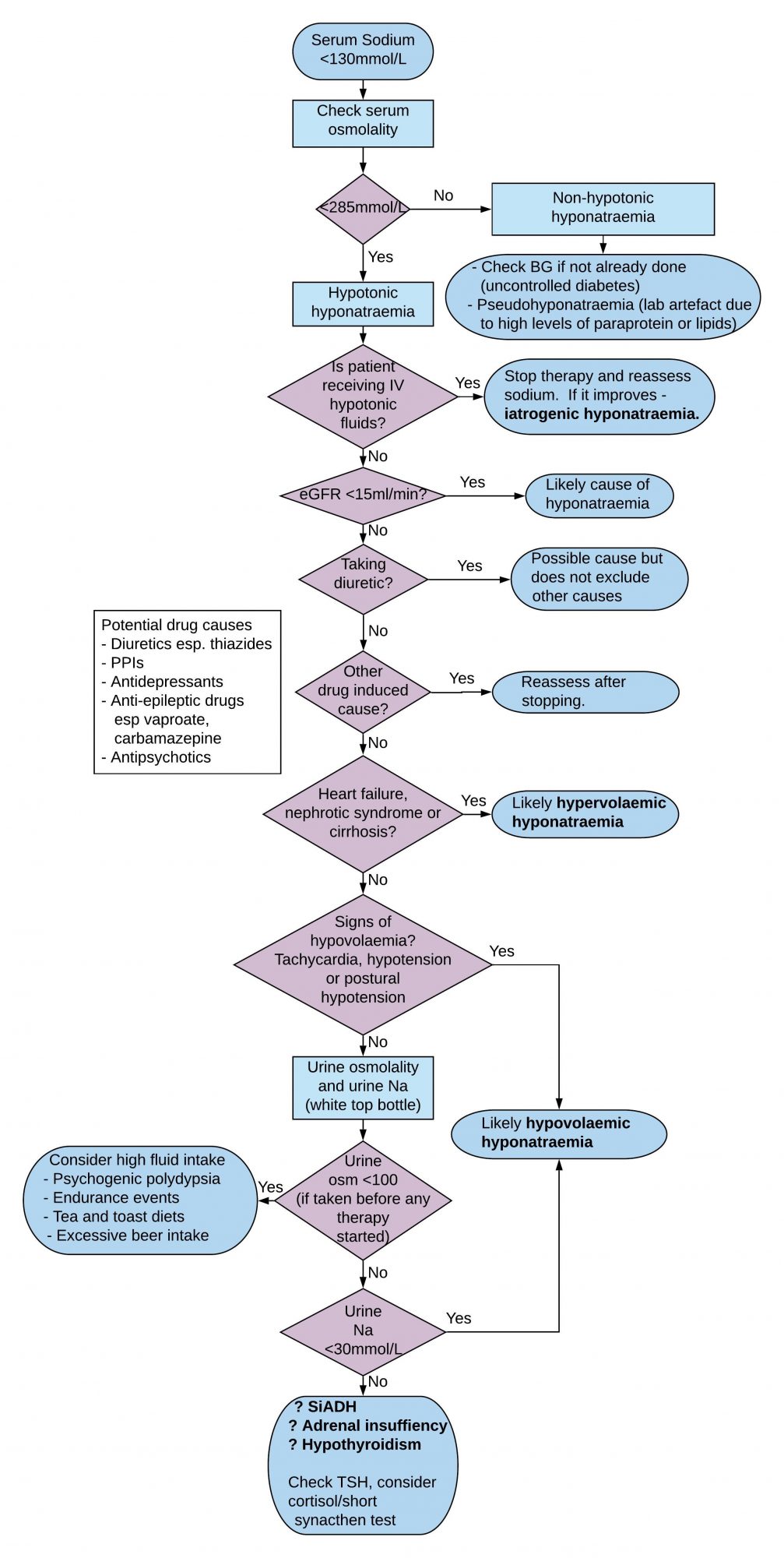

- Check serum osmolality to confirm hypo-osmolar

- Look for reversible causes especially drugs

- Assess patient’s ECF volume status

- Check urine sodium and osmolality

Assess Biochemical Severity

- Mild hyponatraemia is a biochemical finding of serum sodium 130-135 mmol/L for which obvious reversible causes should be considered but which need not generally be investigated further

- Serum sodium <130mmol/l is generally considered significant

- Symptoms/signs usually only occur when sodium <125 mmol/L.

- Acute hyponatraemia is less well tolerated.

- Aetiology is often multifactorial in medical patients

Assess for Cerebral Oedema (Hyponatraemic Encephalopathy)

- Seizures

- Coma

- Altered GCS

Determine Duration of Hyponatraemia if you can

- Those at risk of cerebral oedema have acute hyponatraemia developing within 48 hours ie brain swells because water moves across blood brain barrier before brain has had time to adapt

- Acute hyponatraemia defined as hyponatraemia that is documented to exist <48 hours.

- Hyponatraemia is chronic if documented to exist for at least 48 hours and is considered to be chronic if duration unknown, unless there is clinical evidence of the contrary

Check Serum Osmolality to Confirm Hypo-osmolar

- A measured serum osmolality <275 mOsm/kg always indicates hypotonic hyponatraemia.

- Artefactual hyponatraemia most commonly occurs when blood taken from arm into which dextrose is being infused.

- Can also occur in hyperlipidaemia and hyperproteinaemia (myeloma) because the aqueous fraction of the plasma specimen is reduced by the volume occupied by the lipid/protein molecules. Serum osm normal and treatment of ‘hyponatraemia’ not needed. Also known as pseudohyponatraemia.

- Transient hyponatraemia can also occur with acute hyperglycaemia which expands ECF by its osmotic action with fall in serum Na of 2.4 mmol/l for every 5.5 mmol/l rise in BG.

Possible Drug Induced Causes

- Diuretics – thiazides commonest cause of hyponatraemia (impair free water clearance)

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Anticonvulsants esp carbamazepine and valproate

- Antidepressants

- Antipsychotics

- Anticancer drugs

NB All except diuretics can trigger inappropriate release of ADH

Other Reversible Causes

- Endocrine – hypothyroid, hypoadrenal and hypopituitary

- Psychogenic polydipsia ie excessive water drinking

Assess Extracellular Fluid (ECF) Volume Status

- Volume deplete – sodium deficit greater than water deficit.

- Euvolaemic – water retention only

- Oedematous – sodium retention with relatively greater water retention

Check Urine Sodium and Osmolality

- If urine Na <30mmol/l then it is likely that low effective arterial blood volume is the cause of hypotonic hyponatraemia

- If urine Na ≥30mmol/l then diuretics and/or renal disease likely to be responsible, failing which assess ECF volume which will either be normal eg SIADH, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency; or reduced, eg cerebral salt wasting which is uncommon and usually associated with subarachnoid haemorrhage, subdural haematoma, cerebral injury or brain tumour.

- Urine osm is less useful than urine Na in helping to make a diagnosis

- If urine osm <100 then high fluid intake is the likely cause of hyponatraemia ie drinking too much water and passing large volumes dilute urine.

- If urine osm >700 and patient has SIADH then you are unlikely to correct hyponatraemia simply by water restriction

Causes of SIADH

- Malignancy esp. small cell lung cancer

- Primary brain injury eg. Meningitis, SAH

- Drugs – see list above though not all drug induced causes are due to SIADH

- Infections eg pneumonia

- Hypothyroidism

Criteria for Diagnosis of SIADH

- Clinically euvolaemic

- Low serum sodium <130mmol/l

- Low serum osmolality <270mosm/kg

- Urine Na typically >30mmol/l with normal dietary and salt intake

- Inappropriately concentrated urine osm >100mosm/kg

- No recent diuretic use – interpret biochem with caution if taking diuretic

- Normal serum potassium and blood urea

- Absence of renal, adrenal, thyroid or pituitary insufficiency

Diagnostic Difficulties with Diuretics

- All types of diuretics may be associated with hyponatraemia

- Thiazides are the most likely culprit because they impair free water clearance to a greater extent than others

- The use of diuretics does not exclude other causes of hyponatraemia

- Urine Na <30mmol/l suggests low effective arterial volume even in patients taking diuretics

- Urine Na >30mmol/l should be interpreted with caution if taking diuretic

Five Treatment Scenarios

- Hyponatraemia with Severe Symptoms (seizures, coma, altered GCS) regardless of chronicity

- Acute or Chronic Hyponatraemia (>48 hours or unclear duration) without Severe Symptoms

- Hypervolaemic Hyponatraemia

- Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone (SIADH)

- Fluid status is unclear

Hyponatraemia with Severe Symptoms (seizures, coma, altered GCS) Regardless of Chronicity

- Seek senior input

- Consider if Critical Care transfer is required for monitoring of bloods and clinical status after the infusion. While it is safe to administer hypertonic saline on a general ward, it is essential that the subsequent monitoring and blood tests take place as outlined below; this may be easier to guarantee in a Critical Care environment.

- Give 150ml IV 2.7% hypertonic saline over 20 min.

- Check serum sodium concentration after 20 min

- Repeat 150ml IV 2.7% saline over 20 mins until sodium risen by 5 mmol/L

- Then stop 2.7% saline and give 0.9% saline 83 – 125ml/hour.

- Aim to limit rise in serum sodium in first 24 hours to ≤10 mmol/L and ≤8 mmol/L in each following 24 hours.

- Recheck sodium at 6, 12, 24 and 48 hours.

Acute or Chronic Hyponatraemia without Severe Symptoms

- Ensure there are no sampling or sample handling errors e.g. drip arm venepuncture.

- Recheck serum sodium.

- Stop any non-essential fluids, medications and other factors that can contribute to or provoke the hyponatraemia

- Make diagnostic assessment and treat underlying cause

- In mild hyponatraemia (Na 130-135mmol/l), there is no need to treat with the sole aim of increasing the serum sodium

- If hypovolaemic start IV 0.9% saline 125-250ml/hr depending on severity of fluid deficit

- Recheck serum sodium after 4 hours to determine trend.

- Aim to limit rise in serum sodium in first 24 hours to ≤ 10 mmol/L and ≤ 8mmol/L in each following 24 hours

- NB Risk of Central Pontine Myelinolysis if serum sodium corrected too quickly – see below

- Note that in case of haemodynamic instability, the need for rapid fluid resuscitation overrides the risk of an overly rapid increase in serum sodium concentration

Hypervolaemic Hyponatraemia

- There is insufficient data to suggest that increasing serum sodium improves patient outcomes in this group

- The European Clinical Practice Guideline suggests not treating simply to raise the serum sodium unless this is <125mmol/l

- These patients may require or already be taking a diuretic

- Could consider fluid restriction as a means of reducing further fluid overload

SIADH

- Restrict fluid intake to 1000-1200ml daily as first-line treatment in patients without severe symptoms

- Give combination of low dose loop diuretics and oral sodium chloride if fluid restriction alone fails. The idea here is to get rid of excess water with frusemide while increasing sodium levels with slow sodium.

- The dose of Slow Sodium is 4 tabs bd initially where 1 tab slow sodium contains 600mg NaCl or 10mmol Na

- Lithium, demeclocycline and vasopressin receptor antagonists eg tolvaptan not routinely recommended.

If Fluid Status is Unclear

- Give therapeutic trial of saline 0.9% 1 litre over 12 hours

- Recheck U&E after 6 hours

- Serum Na should increase if hypovolaemic

- Patients with SIADH don’t improve or may worsen – stop fluids if this is the case

Central Pontine Myelinolysis (CPM)

- This is a neurological disorder that most frequently occurs after too rapid medical correction of sodium hyponatremia.

- The rapid rise in sodium concentration pulls water from brain cells which leads, through a mechanism that is only partly understood, to the destruction of myelin, the substance that normally protects nerve fibers.

- Certain areas of the brain are particularly susceptible to myelinolysis, especially the pons.

- Symptoms, which begin to appear 2 to 3 days after hyponatremia is corrected, include a depressed level of awareness, dysarthria or mutism, and dysphagia.

- Additional symptoms often arise over the next 1-2 weeks, including impaired thinking, arm and leg weakness, stiffness, impaired sensation, and poor coordination.

- At its most severe, myelinolysis can lead to coma, “locked-in” syndrome (the complete paralysis of all of the voluntary muscles in the body except for those that control the eyes), and death.

Links

Content updated by Sian Finlay